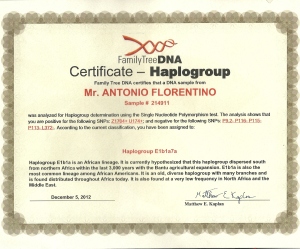

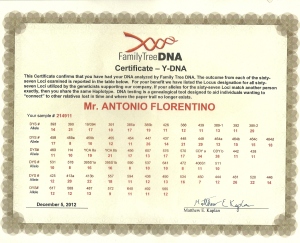

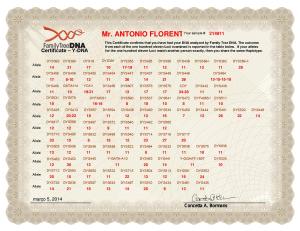

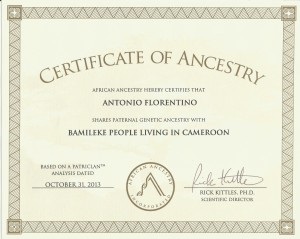

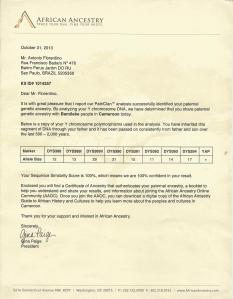

Meu Pai Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a, 100% Tribo Bamileke de Cameroona

MEU PAI haplogrupo Y-DNA E1b1a7a

MEU PAI haplogrupo Y-DNA E1b1a7a

Meu Pai Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a, 100% Tribo Bamileke de Camarões

Meu Pai Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a, 100% Tribo Bamileke de Camarões

Meu Pai Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a, 100% Tribo Bamileke de Camarões

Meu Pai Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a, 100% Tribo Bamileke de Camarões

Ramsés III

Origem: Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre

| Ramsés III | |

|---|---|

| Ramsés III, Ramsés III | |

Alívio do santuário do templo de Khonsu em Karnak representando Ramsés III

| |

| Faraó do Egito | |

| Reinar | 1186-1155 BC, 20 Dynasty |

| Antecessor | Setnakhte |

| Sucessor | Ramsés IV |

| Consort (s) | Iset Ta-Hemdjert , Tyti , Tiye |

| Crianças | Ramsés IV , Ramsés VI , Ramsés VIII , Amun-her-khepeshef , Meryamun , Pareherwenemef , Khaemwaset , Meryatum , Montuherkhopshef , Pentawere , Duatentopet (?) |

| Pai | Setnakhte |

| Mãe | Tiy-Merenese |

| Morreu | 1155 aC |

| Enterro | KV11 |

| Monumentos | Medinet Habu |

Usimare Ramsés III (também escrito Ramses e Ramsés ) foi o segundo faraó da dinastia XX e é considerado o último grande reino novo rei de exercer nenhuma autoridade substancial sobre o Egito.

Ramsés III era filho de Setnakhte e rainha Tiy-Merenese . Ele provavelmente foi assassinado por um assassino em uma conspiração liderada por uma de suas esposas secundárias e seu filho menor.

Conteúdo

[ hide ]

Nome [ editar ]

Dois nomes principais "Ramsés transliteração como wsr-mꜢ't-r'-MRY-IMN R'-ms-S-ḥḳꜢ-ỉwnw. Eles são normalmente realizados como Usermaatre-meryamun Ramesse-hekaiunu , que significa "Poderoso um dos Ma'at e Ra , Amado de Amun , Ra lhe deu, Régua de Heliopolis ".

Ascensão [ editar ]

Ramsés III Acredita-se que reinou de março 1186 a abril 1155 aC. Isto é baseado em sua data de adesão conhecido de I Shemu dia 26 e sua morte, em 32 Ano III Shemu dia 15, para um reinado de 31 anos, 1 mês e 19 dias. [1] datas alternativas para o seu reinado são 1187-1156 BC .

Em uma descrição de sua coroação de Medinet Habu, quatro pombas foram disse ser "despachado para os quatro cantos do horizonte para confirmar que o viver Horus , Ramsés III, (ainda) na posse de seu trono, que a ordem de Maat prevalece no cosmos e da sociedade ". [2] [3]

Posse de guerra constante [ editar ]

Mais informações: Battle of the Delta e colapso da Idade do Bronze

Durante a sua longa permanência no meio do caos político em torno das Dark Ages gregos , o Egito foi assolada por invasores estrangeiros (incluindo os chamados povos do mar e os líbios ) e experimentou o início de crescentes dificuldades económicas e conflitos internos que acabaria levar ao colapso da dinastia XX. No Ano 5 do seu reinado, os povos do mar, incluindo Peleset , Denyen , Shardana , Meshwesh do mar, e Tjekker , invadiu o Egito por terra e mar. Ramsés III derrotou-os em dois grandes batalhas terrestres e marítimas. Embora os egípcios tinham uma reputação como homens pobres mar lutaram tenazmente. Ramsés cobriam as margens com fileiras de arqueiros que mantiveram-se uma salva contínua de flechas contra os navios inimigos quando eles tentaram aterrar nas margens do Nilo. Em seguida, a marinha egípcia atacou usando ganchos para transportar nos navios inimigos. Na mão brutal para combates corpo que se seguiu, os povos do mar foram completamente derrotados. A Harris Papyrus estado:

Quanto àqueles que alcancei meu fronteira, sua semente não é, seu coração e sua alma estão acabados para todo o sempre. Quanto àqueles que vieram para a frente juntos no mar, a chama completo foi na frente deles na foz do Nilo, enquanto uma paliçada de lanças cercado eles na praia, prostrado na praia, que foi morto, e feito em montes da cabeça à cauda . [4]

Ramsés III afirma que ele incorporou os Povos do Mar povos como sujeito e os instalou no sul da Canaã, embora não haja nenhuma evidência clara nesse sentido; o faraó, incapaz de impedir sua chegada gradual em Canaã, pode ter alegou que foi dele a idéia de deixá-los permanecer neste território. Sua presença em Canaã pode ter contribuído para a formação de novos estados na região, tais como Philistia após o colapso do Império egípcio na Ásia. Ramsés III também foi obrigado a lutar invadindo membros de tribos líbias em duas grandes campanhas no Delta ocidental do Egito em seu Ano 6 e 11, respectivamente Ano. [5]

Turbulência econômica [ editar ]

O custo pesado dessas batalhas esgotado lentamente tesouraria do Egito e contribuiu para o declínio gradual do Império egípcio na Ásia. A gravidade destas dificuldades é sublinhado pelo fato de que a greve primeiro conhecido na história registrada ocorreu durante o ano 29 do reinado de Ramsés III, quando as rações alimentares para favorecidas e de elite túmulo de construtores e artesãos reais do Egito, na aldeia de Set Maat ela imenty Waset (agora conhecido como Deir el Medina ), não poderia ser provisionado. [6] Algo no ar (possivelmente a erupção Hekla 3 ) impediu muita luz solar de alcançar o chão e o crescimento da árvore global também preso por quase duas décadas inteiras até 1140 aC. O resultado no Egito foi uma inflação substancial nos preços dos grãos sob os reinados posteriores de Ramsés VI-VII, enquanto que os preços para as aves e os escravos se manteve constante. [7] Assim, o cooldown afetado os últimos anos de Ramsés III e prejudicada sua capacidade de fornecer uma constante fornecimento de rações de cereais para o trabalhador da comunidade Deir el-Medina.

Estas realidades difíceis são completamente ignorados em monumentos oficiais Ramsés ", muitos dos quais procuram imitar os de seu famoso predecessor, Ramsés II , e que apresentam uma imagem de continuidade e estabilidade. Ele construiu adições importantes para os templos em Luxor e Karnak , e seu templo funerário e complexo administrativo em Medinet-Habu está entre o maior e mais bem preservado no Egito; No entanto, a incerteza dos tempos 'Ramsés resulta das maciças fortificações que foram construídas para incluir o último. No templo egípcio no coração do Egito antes do reinado de Ramsés "nunca teve necessidade de ser protegido de tal maneira.

Conspiracy e morte [ editar ]

Ver artigo principal: conspiração Harem

Graças à descoberta do papiro transcrições do julgamento (datado de Ramsés III), sabe-se agora que houve uma conspiração contra sua vida como resultado de um real conspiração harem durante uma celebração em Medinet Habu . A conspiração foi instigada por Tiye , uma de suas três esposas conhecidas (os outros são Tyti e Iset Ta-Hemdjert ), sobre cujo filho iria herdar o trono. O filho de Tyti, Ramsés Amonhirkhopshef (o futuro Ramsés IV ), era o mais velho e sucessor escolhido por Ramsés III, em preferência ao filho de Tiye Pentaweret .

Os documentos do estudo [8] mostram que muitos indivíduos foram implicados na trama. [9] O principal deles eram rainha Tiy e seu filho Pentaweret , chefe da câmara de Ramsés ", Pebekkamen , sete mordomos reais (a Secretaria de Estado respeitável), dois superintendentes do Tesouro, dois porta-estandartes do Exército, dois escribas reais e um Herald. Há pouca dúvida de que todos os principais conspiradores foram executados.: Alguns dos condenados foi dada a opção de se suicidar (possivelmente por envenenamento), em vez de ser condenado à morte [10] De acordo com os sobreviventes ensaios transcrições, três julgamentos separados foram começou no total, enquanto 38 pessoas foram condenadas à morte. [11] Os túmulos de Tiye e seu filho Pentaweret foram roubados e seus nomes apagados para impedi-los de desfrutar de uma vida após a morte. Os egípcios fizeram um trabalho tão minucioso desta que as únicas referências a eles são os documentos do estudo eo que resta de suas tumbas.

Alguns dos acusados harém mulheres tentaram seduzir os membros do judiciário que eles tentaram, mas foram pegos em flagrante. Os juízes que estavam envolvidos foram severamente punidos. [12]

Não é certo se o plano de assassinato sucedeu desde Ramsés IV , sucessor designado do rei, assumiu o trono após a sua morte, em vez de Pentaweret que estava destinado a ser o principal beneficiário da conspiração palaciana. Além disso, Ramsés III morreu em seu 32º ano antes dos resumos das sentenças foram compostas, [13] mas o mesmo ano em que os documentos do estudo [8] gravar o julgamento e execução dos conspiradores.

Apesar de ter sido muito tempo, acreditou que o corpo de Ramsés do III não apresentaram ferimentos evidentes, [12] uma análise recente da múmia por uma equipe forense alemão, televisionado no documentário Ramsés: Mystery Mummy Rei na Science Channel em 2011, mostrou ataduras excessivos ao redor do pescoço. Uma tomografia computadorizada subseqüente que foi feito no Egito por Ashraf Selim e Sahar Saleem, professores de Radiologia na Universidade do Cairo, revelou que, sob as bandagens era uma faca ferida profunda em toda a garganta, profundo o suficiente para alcançar as vértebras. De acordo com o narrador documentário, "Era uma ferida que ninguém poderia ter sobrevivido." [14] A edição de dezembro de 2012 do British Medical Journal cita a conclusão do estudo da equipe de pesquisadores, liderada pelo Dr. Zahi Hawass , o ex- chefe do Conselho Supremo de Antiguidades do Egito, e sua equipe egípcia, bem como o Dr. Albert Zink, do Instituto de Múmias e do Homem de Gelo da Academia Europeia de Bolzano / Bozen na Itália, que afirmou que conspiradores assassinado Ramsés III faraó por cortar seu . garganta [14] [15] [16] observa Zink em entrevista que:

- "O corte [na garganta de Ramsés III] é ... muito profundo e muito grande, ele realmente vai para baixo quase até o osso (espinha) - que deve ter sido uma lesão letal". [17]

Antes desta descoberta que havia sido especulado que Ramsés III tinha sido morto por meios que não teria deixado uma marca no corpo. Entre os conspiradores eram praticantes de magia, [18] , que poderia muito bem ter usado veneno. Alguns tinham colocar diante de uma hipótese de que uma picada de cobra a partir de uma víbora foi a causa da morte do rei. Sua múmia inclui um amuleto para proteger Ramsés III em vida após a morte de cobras. O servo encarregado de sua comida e bebida também estavam entre os conspiradores cotadas na bolsa, mas também havia outros conspiradores que foram chamados a cobra eo senhor de cobras.

Em um aspecto, os conspiradores certamente falhou. A coroa passou para sucessor designado do rei Ramsés IV. Ramsés III pode ter sido duvidoso quanto ao chances deste último sucedendo-o, uma vez que, na Grande Harris Papyrus , ele implorou Amun para garantir os direitos de seu filho. [19]

Legado [ editar ]

O Grande Harris Papyrus ou Papyrus Harris I , que foi encomendado por seu filho e escolhido o sucessor de Ramsés IV , narra grandes doações este rei da terra, estátuas de ouro e construção monumental para vários templos do Egito na Piramesse , Heliopolis , Memphis , Athribis , Hermopolis , Este , Abydos , Coptos , El Kab e outras cidades da Núbia e Síria. Também registra que o rei enviou uma expedição comercial à Terra de Punt e extraído das minas de cobre de Timna no sul de Canaã. Papiro Harris I registra algumas das atividades Ramsés III:

"Eu mandei meus emissários para a terra de Atika,.. [Ie: Timna] para as grandes minas de cobre que estão lá Seus navios levou-os ao longo e os outros foram por terra em seus burros Ele não tinha sido ouvido falar de uma vez que o (tempo de qualquer anteriormente) rei. suas minas foram encontradas e (eles) produziu cobre que foi carregado por dezenas de milhares em seus navios, e de serem enviados ao seu cuidado para o Egito, e chegar com segurança. " (P. Harris I, 78, 1-4) [20]

Mais notavelmente, Ramsés começou a reconstrução do Templo de Khonsu em Karnak desde os alicerces de um templo antes de Amenhotep III e completou o Templo de Medinet Habu em torno de seu 12º ano. [21] Ele decorou as paredes de seu templo Medinet Habu com cenas de suas batalhas navais e terra, para os povos do mar . Este monumento hoje permanece como um dos templos mais bem preservadas do Império Novo. [22]

A múmia de Ramsés III foi descoberto por antiquários em 1886 e é considerado como a múmia egípcia protótipo em vários filmes de Hollywood. [23] Sua tumba ( KV11 ) é um dos maiores do Vale dos Reis .

Disputa cronológica [ editar ]

Alguns cientistas têm tentado estabelecer um ponto cronológica para este reinado do faraó em 1159 aC, com base em uma datação do "1999 Hekla 3 erupção "do vulcão Hekla, na Islândia. Desde registros contemporâneos mostram que o rei teve dificuldades de aprovisionamento seus operários em Deir el-Medina com suprimentos em seu ano 29, este namoro de Hekla 3 pode conectar seu 28 ou 29 anos de reinado de c. 1159 aC. [24] A discrepância menor de um ano é possível desde que os celeiros do Egito poderia ter tido reservas para lidar com, pelo menos, um único ano ruim das colheitas das culturas após o início do desastre. Isto implica que o reinado do rei teria terminado apenas 3-4 anos mais tarde em torno de 1156 ou 1155 aC. A data rival de "2900 BP" ou c.1000 BC já foi proposto por cientistas com base em um re-exame da camada vulcânica. [25] No entanto, não há datas Egyptologist reinado de Ramsés III até tão tarde quanto 1000 aC.

Genética antiga [ editar ]

De acordo com um estudo genético em dezembro de 2012, Ramsés III pertencia a Y-DNA haplogrupo E1b1a com um East Africa Origin, um haplogrupo ydna que predomina na maioria dos africanos subsaarianos. [26]

Referências [ editar ]

- Ir para cima ^ EF Wente & CC Van Siclen, "A Cronologia do Novo Reino" in Estudos em Honra de George R. Hughes, (SAOC 39) 1976, p.235, ISBN 0-918986-01-X

- Ir para cima ^ Murnane, WJ, United com Eternity: um guia conciso para os Monumentos de Medinet Habu, p. 38, Instituto Oriental, Chicago / Universidade Americana no Cairo Press, 1980.

- Ir para cima ^ Wilfred G. Lambert; AR George; . Irving L. Finkel (2000) Sabedoria, Deuses e Literatura: Estudos em Assyriology em Honra de WG Lambert . Eisenbrauns. pp. 384-. ISBN 978-1-57506-004-0 . Retirado 18 de agosto de 2012 .

- Ir para cima ^ Hasel, Michael G. "Inscrição de Merenptah e Relevos ea Origem de Israel" no Oriente Médio no Sudoeste: Ensaios em homenagem a William G. Dever ", editado por Beth Albprt Hakhai A Anual das Escolas Americana de Pesquisa Oriental 58 Vol 2003, citando Edgerton, WF, e Wilson, John A. 1936. Registros Históricos de Ramsés III, os textos em Medinet Habu, Volumes I e II Estudos em Ancient Oriental Civilization 12. Chicago:. O Instituto Oriental da Universidade de Chicago.

- Ir para cima ^ Nicolas Grimal, A história do antigo Egito, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.271

- Ir para cima ^ William F. Edgerton, as greves em vinte e nove anos de Ramsés III, JNES 10, No. 3 (Julho de 1951), pp. 137-145

- Ir para cima ^ Frank J. Yurco, p.456

- ^ Ir até: um b J. H. Breasted, registos antigos do Egito , parte IV, §§423-456

- Ir para cima ^ James H. Breasted, registos antigos do Egito , parte IV, §§416-417

- Ir para cima ^ James H. Breasted, registos antigos do Egito , parte IV, §§446-450

- Ir para cima ^ Joyce Tyldesley, Chronicle of the Queens do Egito, Thames & Hudson outubro de 2006, p.170

- ^ Ir até: um b Cambridge História Antiga , Cambridge University Press 2000, p.247

- Ir para cima ^ JH Breasted, registos antigos do Egito , p.418

- ^ Ir até: um b Veja também garganta do rei Ramsés III foi cortada, a análise revela . Retirado 2012/12/18.

- Ir para cima ^ British Medical Journal, Estudo revela que a garganta de Faraó foi cortado durante o golpe de Estado , segunda-feira 17 dezembro, 2012

- Ir para cima ^ Hawass, Ismail, Selim, Saleem, Fathalla, Waset, Gad, Saad, Fares, Amer, Gostner, Gad, Pusch, Zink (17 de Dezembro de 2012). "Revisitando a conspiração harém e morte de Ramsés III: antropológica, estudo forense, radiológicos e genética " . British Medical Journal 2012 Natal 2012 . Retirado 19 de dezembro, 2012 .

- Ir para cima ^ AFP (18 de Dezembro de 2012). "enigma assassinato de Faraó resolvido após 3.000 anos" . O Daily Telegraph . Retirado 18 de dezembro de 2012 .

- Ir para cima ^ JH Breasted, registos antigos do Egito , pp.454-456

- Jump up^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §246

- Jump up^ A. J. Peden, The Reign of Ramesses IV, Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1994. p.32 Atika has long been equated with Timna, see here B. Rothenburg, Timna, Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines(1972), pp.201-203 where he also notes the probable port at Jezirat al-Faroun.

- Jump up^ Jacobus Van Dijk, 'The Amarna Period and the later New Kingdom' in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw, Oxford University Press paperback, (2002) p.305

- Jump up^ Van Dijk, p.305

- Jump up^ Bob Brier, The Encyclopedia of Mummies, Checkmark Books, 1998., p.154

- Jump up^ Frank J. Yurco, "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause" in Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente, ed: Emily Teeter & John Larson, (SAOC 58) 1999, pp.456-458

- Jump up^ At first, scholars tried to redate the event to "3000 BP": TOWARDS A HOLOCENE TEPHROCHRONOLOGY FOR SWEDEN, Stefan Wastegǎrd, XVI INQUA Congress, Paper No. 41-13, Saturday, July 26, 2003. Also: Late Holocene solifluction history reconstructed using tephrochronology, Martin P. Kirkbride & Andrew J. Dugmore, Geological Society, London, Special Publications; 2005; v. 242; p. 145-155.

- Jump up^ Hawass at al. 2012, Revisiting the harem conspiracy and death of Ramesses III: anthropological, forensic, radiological, and genetic study. BMJ2012;345doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8268 Published 17 December 2012

Further reading[edit]

- Eric H. Cline and David O'Connor, eds. Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt's Last Hero (University of Michigan Press; 2012) 560 pages; essays by scholars

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ramses III. |

| ||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bamileke_people

Bamileke people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Bazu" redirects here. For the Romanian aviator, see Constantin Cantacuzino.

"Bazu" was also the name of an ancient country in Southwest Asia.

Bamileke dancers in Batié, West Province

Bamileke tamtam

The Bamileke is the ethnic group which is now dominant in Cameroon's West and Northwest Provinces. It is part of the Semi-Bantu (or Grassfields Bantu) ethnic group. The Bamileke are regrouped under several groups, each under the guidance of a chief or fon. Nonetheless, all of these groups have the same ancestors and thus share the same history, culture, and languages. The Bamileke have a population of over 3,500,000 individuals. They speak a number of related languages from the Bantoid branch of the Niger–Congo language family. These languages are closely related, however, and some classifications identify a Bamileke dialect continuum with seventeen or more dialects.

Contents

[hide]

- 1 Organization

- 2 Languages

- 3 History

- 4 Lifestyle and settlement patterns

- 5 References

- 6 Further reading

- 7 External links

Organization[edit]

The Bamileke are organized under several chiefdom (or fondom). Of these, the fondoms of Bafang, Bafoussam, Bandjoun, Bangangté, Bawaju,Dschang, and Mbouda are the most prominent. The Bamileke also share much history and culture with the neighbouring fondoms of the Northwest province and notably the Lebialem region of the Southwest province, but the groups have been divided since their territories were split between the French and English in colonial times.

Languages[edit]

Main article: Bamileke languages

Following Ethnologue classification, we can identify 11 different languages or dialects:

Variants of Ghomala' are spoken in most of the Mifi, Koung-Khi, Hauts-Plateaux departments, the eastern Menoua, and portions of Bamboutos, by 260,000 people (1982, SIL). The main fondoms are Baham, Bafoussam, Bamendjou, Bandjoun.

Towards southwest is spoken Fe'fe' in the Upper Nkam division. The main towns include Bafang, Baku, and Kékem.

Yemba is spoken by 300,000 or more people in 1992. Their lands span most of the Menoua division to the west of the Bandjoun, with their capital at Dschang. Fokoué is another major settlement.

Medumba is spoken in most of the Ndé division, by 210,000 people in 1991, with major settlements at Bangangte and Tonga.

Kwa is spoken between the Ndé and the Littoral province, Ngwe around Fontem in the Southwest province.

Bamileke belongs to the Mbam-Nkam group of Grassfields languages, whose attachment to the Bantu division is still disputed. While some consider it a Bantu or semi-Bantu language, others prefer to include Bamileke in the Niger-Congo group. Bamileke is not a unique language. It seems that Bamileke Medumba stems from Ancient Egyptian and is the root language for many other Bamileke variants.

History[edit]

Main source: “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké” (Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.), by Dieudonné Toukam.ISBN : 978-2-296-11827-0

The Bamileke are the native people three regions of Cameroon, namely West, North-West and South-West. Though greater part of this people are from the West region, it is estimated that over the 1/3 of Bamileke are from the English speaking regions, the majority of which are from the North-West region (there are 123 Bamileke villages in this region, against 06 in the South-West). The Grassfields area therefore encompasses the West and North-West and small part of the South-West region of Cameroon. Apart from the Bamileke, there are other tribes that are historically more or less linked to the Bamileke, such as the Igbo's of Nigeria whether by blood or through certain cultural intercourse, (D. Toukam, “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké”, p. 15).

The Bamileke speak a semi-Bantu language and are related to Bantu peoples. Historically, the Bamun and the Bamileke were united. The founder of this group (Nchare) was the younger brother of the founder of Bafoussam. Bamiléké are a group comprising many tribes. In this group, there are at least eight different cultures, including Dschang, Bafang, Bagangté, Mbouda and Bafoussam.

During the mid-17th century, the Bamiléké people's forefathers left the North to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. They migrated as far south as Foumban. Conquerors came all the way to Foumban to try to impose Islam on them. A war began, pushing some people to leave while others remained, submitting to Islam. This marks the division between the Bamun and Bamiléké people.

Bantu refers to a large, complex linguistic grouping of peoples in Africa. The Cameroon-Bamileke Bantu people cluster encompasses multiple Bantu ethnic groups primarily found in Cameroon, the largest of which is the Bamileke. The Bamileke, whose origins trace to Egypt, migrated to what is now northern Cameroon between the 11th and 14th centuries. In the 17th century they migrated further south and west to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. Today, a majority of peoples within this people cluster are Christians.

German administration[edit]

Germany gained control of "Kamerun" in 1884.

The Germans first applied the term "Bamileke" to the people as administrative shorthand for the people of the region.

French administration and post-independence[edit]

The Bamileke are very dynamic and have a great sense of entrepreneurship. Thus, they can be found in almost all provinces of Cameroon and in the world, mainly as business owner.

In 1955, the colonial French power banned the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) political party, which was claiming the independence of Cameroon. Following that, the French started an offensive against UPC militants. Part of the attacks were done in the West province, region of the Bamileke (Some people considered those attacks as a genocide, given the high number of people killed).[1]

Lifestyle and settlement patterns[edit]

Political structure and agriculture[edit]

Statue of a chief at Bana.

The Bamileke's settlements follow a well organized and structured pattern. Houses of family members are often grouped together, often surrounded by small fields. Men typically clear the fields, but it is largely women who work them. Most work is done with tools such as machetes and hoes. Staple crops include cocoyams, groundnuts and maize.

Bamileke settlement are organized as chiefdoms. The chief, or fon or fong is considered as the spiritual, political, judicial and military leader. The Chief is also considered as the 'Father' of the chiefdom. He thus has great respect from the population. The successor of the 'Father' is chosen among his children. The successor's identity is typically kept secret until the fon's death.

The fon has typically 9 ministers and several other advisers and councils. The ministers are in charge of the crowning of the new fon. The council of ministers, also known as the Council of Notables is called Kamveu. In addition, a "queen mother" or mafo was an important figure for some fons in the past. Below the fon and his advisers lie a number of ward heads, each responsible for a particular portion of the village. Some Bamileke groups also recognise sub-chiefs, or fonte.

Economic activities[edit]

Hut at the chefferie of Bana.

The Bamileke are renowned for their skilled craftsmen and great sense of business. Their artwork is highly praised, though since the colonial period, many traditional arts and crafts have been abandoned. Bamileke are particularly celebrated carvers in wood, ivory, and horn. Chief's compounds are notable for their intricately carved doorframes and columns.

Traditional homes are constructed by first erecting a raffia-pole frame into four square walls. Builders then stuff the resulting holes with grass and cover the whole building with mud. The thatched roof is typically shaped into a tall cone. Nowadays, however, this type of construction is mostly reserved for barns, storage buildings, and gathering places for various traditional secret societies. Instead, modern Bamileke homes are made of bricks of either sun-dried mud or of concrete. Roofs are of metal sheeting.

Bamileke have some of Cameroon's most prominent entrepreneurs. Bamileke are also found in all other professional areas as artisans, farmers, traders, and skilled professionals. They thus play an important role in the economic development of Cameroon.

Religious beliefs[edit]

During the colonial period, parts of the Bamileke adopted Christianity. Some of them practice Islam toward the border with the Adamawa Tikar and the Bamun. The Bamileke have worn elephant mask for dance ceremonies or funerals.[citation needed]

Succession and kinship patterns[edit]

The Bamileke trace ancestry, inheritance and succession through the male line, and children belong to the fondom of their father. After a man's death, all of his possessions typically go to a single, male heir. Polygamy (more specifically, polygyny) is practiced, and some important individuals may have literally hundreds of wives. Marriages typically involve a bride price to be paid to the bride's family.

It is argued that the Bamileke inheritance customs contributed to their success in the modern world:

"Succession and inheritance rules are determined by the principle of patrilineal descent. According to custom, the eldest son is the probable heir, but a father may choose any one of his sons to succeed him. An heir takes his dead father's name and inherits any titles held by the latter, including the right to membership in any societies to which he belonged. And, until the mid-1960s, when the law governing polygamy was changed, the heir also inherited his father's wives--a considerable economic responsibility. The rights in land held by the deceased were conferred upon the heir subject to the approval of the chief, and, in the event of financial inheritance, the heir was not obliged to share this with other family members. The ramifications of this are significant. First, dispossessed family members were not automatically entitled to live off the wealth of the heir. Siblings who did not share in the inheritance were, therefore, strongly encouraged to make it on their own through individual initiative and by assuming responsibility for earning their livelihood. Second, this practice of individual responsibility in contrast to a system of strong family obligations prevented a drain on individual financial resources. Rather than spend all of the inheritance maintaining unproductive family members, the heir could, in the contemporary period, utilize his resources in more financially productive ways such as for savings and investment. [...] Finally, the system of inheritance, along with the large-scale migration resulting from population density and land pressures, is one of the internal incentives that accounts for Bamileke success in the nontraditional world".[2]

Donald L. Horowitz also attributes the economic success of the Bamileke to their inheritance customs, arguing that it encouraged younger sons to seek their own living abroad. He wrote in "Ethnic groups in conflict": "Primogeniture among the Bamileke and matrilineal inheritance among the Minangkabau of Indonesia have contributed powerfully to the propensity of males from both groups to migrate out of their home region in search of opportunity".[3]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Owono, Julie (25 January 2012). "Unspoken history: The last genocide of the 20th century". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Jump up^ A.I.D. Evaluation Special Study No. 15 THE PRIVATE SECTOR: - Individual Initiative, And Economic Growth In An African Plural Society The Bamileke Of Cameroonhttp://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaal016.pdf

- Jump up^ http://books.google.es/books?id=Q82saX1HVQYC&pg=PA155&lpg=PA155&dq=%22Primogeniture%22+%22Bamileke%22&source=bl&ots=JMOOcssnc-&sig=BtkVUJrmKPp6ZW48t5fyMx_X4Ak&hl=es&sa=X&ei=UgeLUuChHMSv7AbwnYCYBw&ved=0CEQQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=%22Primogeniture%22%20%22Bamileke%22&f=false

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2010), Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké, Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2008), Parlons bamiléké. Langue et culture de Bafoussam, Paris: L'Harmattan, 255p.

- Fanso, V.G. (1989) Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989.

- Neba, Aaron, Ph.D. (1999) Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon, 3rd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1999.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996) History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbé: Presbook, 1996.

Further reading[edit]

- Knöpfli, Hans (1997—2002) Crafts and Technologies: Some Traditional Craftsmen and Women of the Western Grassfields of Cameroon. 4 vols. Basel, Switzerland: Basel Mission.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bamileke. |

http://www.shavei.org/category/communities/other_communities/africa/cameroon/?lang=en

Cameroon

There are some who believe that an ancient Jewish presence may have at one time existed in Cameroon via merchants who arrived from Egypt for trade. According to these accounts, the early communities in Cameroon observed rituals such as separation of dairy and meat products, as well as wearingtefillin.

There are also claims that Jews migrated into Cameroon much later, after being forced southward due to the Islamic conquests of North Africa.

The main claims of a Jewish presence in Cameroon are made by Rabbi Yisrael Oriel, formerly known as Bodol Ngimbus-Ngimbus. He was born into the Ba-Saa tribe; the word “Ba-Saa,” he says, is from the Hebrew for “on a journey.” Oriel also claims to be a Levite descended from Moses.

According to Oriel in 1920 there were 400,000 “Israelites” in Cameroon, but by 1962 the number had decreased to 167,000 due to conversions to Christianity and Islam. He admitted that these tribes had not been accepted according to Jewish law, although he claimed that he could still prove their Jewish status from medieval rabbinic sources.

A website called “Jewish Cameroon” provides more details. Oriel describes the period between 1920 and 1962 as “a ‘spiritual Shoah.’ Because of intense missionary activity, it was like the Soviet Union where Jews had no permission for Jewish education, no batei din (Jewish courts), synagogues or sifrei (books of the) Torah. Everything was taught by oral tradition, Oriel says.”

Oriel’s father, the website continues, Hassid Peniel Moshe Shlomo (Ngimbus Nemb Yemba) was a textile manufacturer, scribe, mohel (ritual circumciser) and tribal leader. Oriel says his father was imprisoned 50 times for teaching his traditional Jewish beliefs. In 1932 he ran away from a Catholic school because they had wanted him to train for the priesthood.

Oriel’s grandfather reportedly built a synagogue in Cameroon, but that it is now in ruins. Oriel’s grandfather is said to have been the last gabbai of the synagogue.

Oriel’s mother, who he calls Orah Leah (her given name was Ngo Ngog Lum), had a large kitchen in which milk and meat were separated – by six meters, he says. Shortly before his mother died in 1957, she told him: “My beloved child, one day you will go to ‘Yesulmi’.” It was not till 1980 that he realized that she must have meant Jerusalem.

Oriel left Cameroon in the early 1960s after the country received independence. He studied law and international relations in France.

Oriel formally converted to Judaism some 20 years and was ordained as a rabbi in Israel, to which he made aliyah and where he lived briefly. He now resides in London and prays at the Persian Hebrew congregation and the Moroccan “Hida” Synagogue and Bekt Midrash on East Bank, Stamford Hill, London. You can see a photo of Oriel here.

Oriel remains active in trying to bring Judaism to Cameroon, as well as neighboring Nigeria, and to bring what he claims are “the 10 lost tribes” back to the fold. There is much more about Oriel on the Jewish Cameroonsite, including some more outlandish claims and grievances Oriel has against the established Jewish community.

Other reported Jewish tribes in Cameroon are said to include Haussa, descended from the tribe of Issachar, who were forced to convert to Islam in the eighth and ninth centuries, and the Bamileke who are largely Christian today. Nchinda Gideon claims that these early immigrants built synagogues but there are no records of them in Cameroon today.

American actor Yaphet Kotto, whose parents emigrated from Cameroon to the United States, claims Jewish descent. Kotto, who died in 2008, had a starring role in the television series Homicide: Life on the Streetand also appeared in films such as Alien and the James Bond movie Live and Let Die.

In his autobiography entitled Royalty, Kotto writes that his father was “the crown prince of Cameroon” and that he was an observant Jew who spoke Hebrew. Kotto’s mother reportedly converted to Judaism before marrying his father. Kotto also says that his great-grandfather, King Alexander Bell, ruled the Douala region of Cameroon in the late 19th century and was also a practicing Jew.

Kotto says that his paternal family originated from Israel and migrated to Egypt and then Cameroon, and have been African Jews for many generations. Kotto writes that being black and Jewish gave other children even more reason to pick on him growing up in New York City. He says that he went to synagogue and occasionally wore a yarmulke when he was younger.

A very tenuous, primarily linguistic connection between Cameroon and ancient Israel can be found through another tribe known as the Bankon who live in the Littoral region of Cameroon. The word “Ban” – also pronounced “Kon” – means “son of prince” in Assyrian, an Aramaic dialect. In her work The Negro-African Languages, a French scholar, Lilias Homburger, points out that the Bankon’s language is “Kum” which may derive from the Hebrew for “arise” or “get up!” Further, the Assyrians called the House of Israel by the name of Kumri.

More recent Jewish presence in Cameroon

Twelve years ago, 1,000 Evangelical Christians in Cameroon decided they no longer wanted to practice Christianity and turned instead to Judaism, embracingpractices from the bible. Their informal conversion to Judaism is similar to Uganda’sAbuyadaya Jewish community which, in 1919, also moved towards Judaism even though, in both cases, they had never met any Jews and had no in-person guidance or mentoring in developing their Jewish identity. The Cameroon community calls itself Beth Yeshourun and is very small, with only 60 members in total.

Much of what the community has learned has been via the Internet, including downloading prayers and songs. Some of the community has taught itself Hebrew; others pray in a mixture of French and transliterated Hebrew.

Rabbis Bonita and Gerald Sussman visited the community in 2010. Their description is presented in detail on the Kulanu website. Here are a few highlights from that trip.

- The Sussmans chose to trust the community’s level of kashrut, eating primarily fish and vegetables.

- Community members washed their hands ritually before eating bread and a meal.

- The community was fairly knowledgeable about Jewish tradition and asked the Sussman’s many questions about Jewish law, such as what to eat at a family event that is not kosher, when do you pray the Minchaafternoon service when you are traveling, and must you stand during the Amidah prayers if you are sick?

- The Shabbat service, held in the Beth Yeshourun synagogue, was remarkable similar to today’s mainstream Orthodox Judaism, including the full Kabbalat Shabbat, the singing of Lecha Dodi and even the closing Yigdal prayer.

- On Shabbat day, the community sang a mixture of songs in the local language as well as modern Israeli songs such as Jerusalem of Gold.

- The community prays three times a day and holds Torah study sessions twice a week, using material gleaned from the web.

- The community has created its own siddur (prayer book) of 150 pages, also by downloading content from the Internet.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bamileke_people

Bamileke people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Bazu" redirects here. For the Romanian aviator, see Constantin Cantacuzino.

"Bazu" was also the name of an ancient country in Southwest Asia.

Bamileke dancers in Batié, West Province

Bamileke tamtam

The Bamileke is the ethnic group which is now dominant in Cameroon's West and Northwest Provinces. It is part of the Semi-Bantu (or Grassfields Bantu) ethnic group. The Bamileke are regrouped under several groups, each under the guidance of a chief or fon. Nonetheless, all of these groups have the same ancestors and thus share the same history, culture, and languages. The Bamileke have a population of over 3,500,000 individuals. They speak a number of related languages from the Bantoid branch of the Niger–Congo language family. These languages are closely related, however, and some classifications identify a Bamileke dialect continuum with seventeen or more dialects.

Contents

[hide]

- 1 Organization

- 2 Languages

- 3 History

- 4 Lifestyle and settlement patterns

- 5 References

- 6 Further reading

- 7 External links

Organization[edit]

The Bamileke are organized under several chiefdom (or fondom). Of these, the fondoms of Bafang, Bafoussam, Bandjoun, Bangangté, Bawaju,Dschang, and Mbouda are the most prominent. The Bamileke also share much history and culture with the neighbouring fondoms of the Northwest province and notably the Lebialem region of the Southwest province, but the groups have been divided since their territories were split between the French and English in colonial times.

Languages[edit]

Main article: Bamileke languages

Following Ethnologue classification, we can identify 11 different languages or dialects:

Variants of Ghomala' are spoken in most of the Mifi, Koung-Khi, Hauts-Plateaux departments, the eastern Menoua, and portions of Bamboutos, by 260,000 people (1982, SIL). The main fondoms are Baham, Bafoussam, Bamendjou, Bandjoun.

Towards southwest is spoken Fe'fe' in the Upper Nkam division. The main towns include Bafang, Baku, and Kékem.

Yemba is spoken by 300,000 or more people in 1992. Their lands span most of the Menoua division to the west of the Bandjoun, with their capital at Dschang. Fokoué is another major settlement.

Medumba is spoken in most of the Ndé division, by 210,000 people in 1991, with major settlements at Bangangte and Tonga.

Kwa is spoken between the Ndé and the Littoral province, Ngwe around Fontem in the Southwest province.

Bamileke belongs to the Mbam-Nkam group of Grassfields languages, whose attachment to the Bantu division is still disputed. While some consider it a Bantu or semi-Bantu language, others prefer to include Bamileke in the Niger-Congo group. Bamileke is not a unique language. It seems that Bamileke Medumba stems from Ancient Egyptian and is the root language for many other Bamileke variants.

History[edit]

Main source: “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké” (Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.), by Dieudonné Toukam.ISBN : 978-2-296-11827-0

The Bamileke are the native people three regions of Cameroon, namely West, North-West and South-West. Though greater part of this people are from the West region, it is estimated that over the 1/3 of Bamileke are from the English speaking regions, the majority of which are from the North-West region (there are 123 Bamileke villages in this region, against 06 in the South-West). The Grassfields area therefore encompasses the West and North-West and small part of the South-West region of Cameroon. Apart from the Bamileke, there are other tribes that are historically more or less linked to the Bamileke, such as the Igbo's of Nigeria whether by blood or through certain cultural intercourse, (D. Toukam, “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké”, p. 15).

The Bamileke speak a semi-Bantu language and are related to Bantu peoples. Historically, the Bamun and the Bamileke were united. The founder of this group (Nchare) was the younger brother of the founder of Bafoussam. Bamiléké are a group comprising many tribes. In this group, there are at least eight different cultures, including Dschang, Bafang, Bagangté, Mbouda and Bafoussam.

During the mid-17th century, the Bamiléké people's forefathers left the North to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. They migrated as far south as Foumban. Conquerors came all the way to Foumban to try to impose Islam on them. A war began, pushing some people to leave while others remained, submitting to Islam. This marks the division between the Bamun and Bamiléké people.

Bantu refers to a large, complex linguistic grouping of peoples in Africa. The Cameroon-Bamileke Bantu people cluster encompasses multiple Bantu ethnic groups primarily found in Cameroon, the largest of which is the Bamileke. The Bamileke, whose origins trace to Egypt, migrated to what is now northern Cameroon between the 11th and 14th centuries. In the 17th century they migrated further south and west to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. Today, a majority of peoples within this people cluster are Christians.

German administration[edit]

Germany gained control of "Kamerun" in 1884.

The Germans first applied the term "Bamileke" to the people as administrative shorthand for the people of the region.

French administration and post-independence[edit]

The Bamileke are very dynamic and have a great sense of entrepreneurship. Thus, they can be found in almost all provinces of Cameroon and in the world, mainly as business owner.

In 1955, the colonial French power banned the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) political party, which was claiming the independence of Cameroon. Following that, the French started an offensive against UPC militants. Part of the attacks were done in the West province, region of the Bamileke (Some people considered those attacks as a genocide, given the high number of people killed).[1]

Lifestyle and settlement patterns[edit]

Political structure and agriculture[edit]

Statue of a chief at Bana.

The Bamileke's settlements follow a well organized and structured pattern. Houses of family members are often grouped together, often surrounded by small fields. Men typically clear the fields, but it is largely women who work them. Most work is done with tools such as machetes and hoes. Staple crops include cocoyams, groundnuts and maize.

Bamileke settlement are organized as chiefdoms. The chief, or fon or fong is considered as the spiritual, political, judicial and military leader. The Chief is also considered as the 'Father' of the chiefdom. He thus has great respect from the population. The successor of the 'Father' is chosen among his children. The successor's identity is typically kept secret until the fon's death.

The fon has typically 9 ministers and several other advisers and councils. The ministers are in charge of the crowning of the new fon. The council of ministers, also known as the Council of Notables is called Kamveu. In addition, a "queen mother" or mafo was an important figure for some fons in the past. Below the fon and his advisers lie a number of ward heads, each responsible for a particular portion of the village. Some Bamileke groups also recognise sub-chiefs, or fonte.

Economic activities[edit]

Hut at the chefferie of Bana.

The Bamileke are renowned for their skilled craftsmen and great sense of business. Their artwork is highly praised, though since the colonial period, many traditional arts and crafts have been abandoned. Bamileke are particularly celebrated carvers in wood, ivory, and horn. Chief's compounds are notable for their intricately carved doorframes and columns.

Traditional homes are constructed by first erecting a raffia-pole frame into four square walls. Builders then stuff the resulting holes with grass and cover the whole building with mud. The thatched roof is typically shaped into a tall cone. Nowadays, however, this type of construction is mostly reserved for barns, storage buildings, and gathering places for various traditional secret societies. Instead, modern Bamileke homes are made of bricks of either sun-dried mud or of concrete. Roofs are of metal sheeting.

Bamileke have some of Cameroon's most prominent entrepreneurs. Bamileke are also found in all other professional areas as artisans, farmers, traders, and skilled professionals. They thus play an important role in the economic development of Cameroon.

Religious beliefs[edit]

During the colonial period, parts of the Bamileke adopted Christianity. Some of them practice Islam toward the border with the Adamawa Tikar and the Bamun. The Bamileke have worn elephant mask for dance ceremonies or funerals.[citation needed]

Succession and kinship patterns[edit]

The Bamileke trace ancestry, inheritance and succession through the male line, and children belong to the fondom of their father. After a man's death, all of his possessions typically go to a single, male heir. Polygamy (more specifically, polygyny) is practiced, and some important individuals may have literally hundreds of wives. Marriages typically involve a bride price to be paid to the bride's family.

It is argued that the Bamileke inheritance customs contributed to their success in the modern world:

"Succession and inheritance rules are determined by the principle of patrilineal descent. According to custom, the eldest son is the probable heir, but a father may choose any one of his sons to succeed him. An heir takes his dead father's name and inherits any titles held by the latter, including the right to membership in any societies to which he belonged. And, until the mid-1960s, when the law governing polygamy was changed, the heir also inherited his father's wives--a considerable economic responsibility. The rights in land held by the deceased were conferred upon the heir subject to the approval of the chief, and, in the event of financial inheritance, the heir was not obliged to share this with other family members. The ramifications of this are significant. First, dispossessed family members were not automatically entitled to live off the wealth of the heir. Siblings who did not share in the inheritance were, therefore, strongly encouraged to make it on their own through individual initiative and by assuming responsibility for earning their livelihood. Second, this practice of individual responsibility in contrast to a system of strong family obligations prevented a drain on individual financial resources. Rather than spend all of the inheritance maintaining unproductive family members, the heir could, in the contemporary period, utilize his resources in more financially productive ways such as for savings and investment. [...] Finally, the system of inheritance, along with the large-scale migration resulting from population density and land pressures, is one of the internal incentives that accounts for Bamileke success in the nontraditional world".[2]

Donald L. Horowitz also attributes the economic success of the Bamileke to their inheritance customs, arguing that it encouraged younger sons to seek their own living abroad. He wrote in "Ethnic groups in conflict": "Primogeniture among the Bamileke and matrilineal inheritance among the Minangkabau of Indonesia have contributed powerfully to the propensity of males from both groups to migrate out of their home region in search of opportunity".[3]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Owono, Julie (25 January 2012). "Unspoken history: The last genocide of the 20th century". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Jump up^ A.I.D. Evaluation Special Study No. 15 THE PRIVATE SECTOR: - Individual Initiative, And Economic Growth In An African Plural Society The Bamileke Of Cameroonhttp://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaal016.pdf

- Jump up^ http://books.google.es/books?id=Q82saX1HVQYC&pg=PA155&lpg=PA155&dq=%22Primogeniture%22+%22Bamileke%22&source=bl&ots=JMOOcssnc-&sig=BtkVUJrmKPp6ZW48t5fyMx_X4Ak&hl=es&sa=X&ei=UgeLUuChHMSv7AbwnYCYBw&ved=0CEQQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=%22Primogeniture%22%20%22Bamileke%22&f=false

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2010), Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké, Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2008), Parlons bamiléké. Langue et culture de Bafoussam, Paris: L'Harmattan, 255p.

- Fanso, V.G. (1989) Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989.

- Neba, Aaron, Ph.D. (1999) Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon, 3rd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1999.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996) History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbé: Presbook, 1996.

Further reading[edit]

- Knöpfli, Hans (1997—2002) Crafts and Technologies: Some Traditional Craftsmen and Women of the Western Grassfields of Cameroon. 4 vols. Basel, Switzerland: Basel Mission.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bamileke. |

http://www.shavei.org/category/communities/other_communities/africa/cameroon/?lang=en

Cameroon

There are some who believe that an ancient Jewish presence may have at one time existed in Cameroon via merchants who arrived from Egypt for trade. According to these accounts, the early communities in Cameroon observed rituals such as separation of dairy and meat products, as well as wearingtefillin.

There are also claims that Jews migrated into Cameroon much later, after being forced southward due to the Islamic conquests of North Africa.

The main claims of a Jewish presence in Cameroon are made by Rabbi Yisrael Oriel, formerly known as Bodol Ngimbus-Ngimbus. He was born into the Ba-Saa tribe; the word “Ba-Saa,” he says, is from the Hebrew for “on a journey.” Oriel also claims to be a Levite descended from Moses.

According to Oriel in 1920 there were 400,000 “Israelites” in Cameroon, but by 1962 the number had decreased to 167,000 due to conversions to Christianity and Islam. He admitted that these tribes had not been accepted according to Jewish law, although he claimed that he could still prove their Jewish status from medieval rabbinic sources.

A website called “Jewish Cameroon” provides more details. Oriel describes the period between 1920 and 1962 as “a ‘spiritual Shoah.’ Because of intense missionary activity, it was like the Soviet Union where Jews had no permission for Jewish education, no batei din (Jewish courts), synagogues or sifrei (books of the) Torah. Everything was taught by oral tradition, Oriel says.”

Oriel’s father, the website continues, Hassid Peniel Moshe Shlomo (Ngimbus Nemb Yemba) was a textile manufacturer, scribe, mohel (ritual circumciser) and tribal leader. Oriel says his father was imprisoned 50 times for teaching his traditional Jewish beliefs. In 1932 he ran away from a Catholic school because they had wanted him to train for the priesthood.

Oriel’s grandfather reportedly built a synagogue in Cameroon, but that it is now in ruins. Oriel’s grandfather is said to have been the last gabbai of the synagogue.

Oriel’s mother, who he calls Orah Leah (her given name was Ngo Ngog Lum), had a large kitchen in which milk and meat were separated – by six meters, he says. Shortly before his mother died in 1957, she told him: “My beloved child, one day you will go to ‘Yesulmi’.” It was not till 1980 that he realized that she must have meant Jerusalem.

Oriel left Cameroon in the early 1960s after the country received independence. He studied law and international relations in France.

Oriel formally converted to Judaism some 20 years and was ordained as a rabbi in Israel, to which he made aliyah and where he lived briefly. He now resides in London and prays at the Persian Hebrew congregation and the Moroccan “Hida” Synagogue and Bekt Midrash on East Bank, Stamford Hill, London. You can see a photo of Oriel here.

Oriel remains active in trying to bring Judaism to Cameroon, as well as neighboring Nigeria, and to bring what he claims are “the 10 lost tribes” back to the fold. There is much more about Oriel on the Jewish Cameroonsite, including some more outlandish claims and grievances Oriel has against the established Jewish community.

Other reported Jewish tribes in Cameroon are said to include Haussa, descended from the tribe of Issachar, who were forced to convert to Islam in the eighth and ninth centuries, and the Bamileke who are largely Christian today. Nchinda Gideon claims that these early immigrants built synagogues but there are no records of them in Cameroon today.

American actor Yaphet Kotto, whose parents emigrated from Cameroon to the United States, claims Jewish descent. Kotto, who died in 2008, had a starring role in the television series Homicide: Life on the Streetand also appeared in films such as Alien and the James Bond movie Live and Let Die.

In his autobiography entitled Royalty, Kotto writes that his father was “the crown prince of Cameroon” and that he was an observant Jew who spoke Hebrew. Kotto’s mother reportedly converted to Judaism before marrying his father. Kotto also says that his great-grandfather, King Alexander Bell, ruled the Douala region of Cameroon in the late 19th century and was also a practicing Jew.

Kotto says that his paternal family originated from Israel and migrated to Egypt and then Cameroon, and have been African Jews for many generations. Kotto writes that being black and Jewish gave other children even more reason to pick on him growing up in New York City. He says that he went to synagogue and occasionally wore a yarmulke when he was younger.

A very tenuous, primarily linguistic connection between Cameroon and ancient Israel can be found through another tribe known as the Bankon who live in the Littoral region of Cameroon. The word “Ban” – also pronounced “Kon” – means “son of prince” in Assyrian, an Aramaic dialect. In her work The Negro-African Languages, a French scholar, Lilias Homburger, points out that the Bankon’s language is “Kum” which may derive from the Hebrew for “arise” or “get up!” Further, the Assyrians called the House of Israel by the name of Kumri.

More recent Jewish presence in Cameroon

Twelve years ago, 1,000 Evangelical Christians in Cameroon decided they no longer wanted to practice Christianity and turned instead to Judaism, embracingpractices from the bible. Their informal conversion to Judaism is similar to Uganda’sAbuyadaya Jewish community which, in 1919, also moved towards Judaism even though, in both cases, they had never met any Jews and had no in-person guidance or mentoring in developing their Jewish identity. The Cameroon community calls itself Beth Yeshourun and is very small, with only 60 members in total.

Much of what the community has learned has been via the Internet, including downloading prayers and songs. Some of the community has taught itself Hebrew; others pray in a mixture of French and transliterated Hebrew.

Rabbis Bonita and Gerald Sussman visited the community in 2010. Their description is presented in detail on the Kulanu website. Here are a few highlights from that trip.

- The Sussmans chose to trust the community’s level of kashrut, eating primarily fish and vegetables.

- Community members washed their hands ritually before eating bread and a meal.

- The community was fairly knowledgeable about Jewish tradition and asked the Sussman’s many questions about Jewish law, such as what to eat at a family event that is not kosher, when do you pray the Minchaafternoon service when you are traveling, and must you stand during the Amidah prayers if you are sick?

- The Shabbat service, held in the Beth Yeshourun synagogue, was remarkable similar to today’s mainstream Orthodox Judaism, including the full Kabbalat Shabbat, the singing of Lecha Dodi and even the closing Yigdal prayer.

- On Shabbat day, the community sang a mixture of songs in the local language as well as modern Israeli songs such as Jerusalem of Gold.

- The community prays three times a day and holds Torah study sessions twice a week, using material gleaned from the web.

- The community has created its own siddur (prayer book) of 150 pages, also by downloading content from the Internet.

77.82% (West African) Yoruba

8.11% (Middle East) Jewish, Palestinian, Bedouin, Bedouin South, Druze

14.07% (Europe) Finnish and Russian

NOTE: This test is an autosomal test and this test will go back 6-8 generations, which is about 200 years ago.

Also FTDNA list geographically Sudan and Egypt as part of the Middle East, although the countries of North Africa, which has Indigenous Nubians and Bedouins as well as an influx of Arab and Middle Eastern populations.

My middle eastern descent groups Levante share with the Druze, who are a monotheistic religious community, found primarily in Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan, which emerged during the 11th century from Ismailism. The Druze people reside primarily in Syria, Lebanon and Israel. which is home to about 20,000 Druze.

The Institute of Druze Studies estimates that 40% -50% of Druze live in Syria, 30% to 40% in Lebanon, 6% -7% in Israel, and 1% to 2% in Jordan.

Large communities of expatriate Druze also live outside the Middle East in Australia, Canada, Europe, Latin America and West Africa. They use the Arabic language and follow a social pattern very similar to the other peoples of the eastern Mediterranean region.

Family Locator My ancestry is shared by both parents and grandparents and Great Great on both sides.

This test should not be confused with a Test of ancestral origin, as mtDNA and Y-chromosome test.

My autosomal:

My autosomal:

214,911 autosomal-it-results.csv

More likely adjustment of 24.9% (+ - 14.4%) Africa (subcontinents various)

and 58.2% (+ - 15.3%) Africa (all West African)

that is 83.1%, total Africa

and 16.9% (+ - 1.2%) Europe (various sub-continents)

The following are possible population sets and their fractions,

probably on top

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.439 = 0.382 = 0.179 or Russian

Maasai = 0.152 Yoruba = 0.671 = 0.177 or Russian

The Ethiopian-= 0.129 = 0.711 = 0.160 Finland Yoruba or

The Ethiopian-Yoruba = 0.129 = 0.710 = 0.161 or Russian

Bantu Ke = 0.431 = 0.391 = 0.178 Mandenka or Finland

Maasai = 0.149 Yoruba = 0.675 = 0.176 Finland or

The Ethiopian-Yoruba = 0.116 = 0.734 = 0.150 Finland or

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.396 = 0.424 = 0.180 or Irish

T-Ethiopian Yoruba = 0.115 = 0.734 = 0.151 Finland or

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.433 = 0.389 = 0.178 Belarus

Western Europe, but it is also very possible.

3.2% Native American (European subtracts).

More likely adjustment of 24.9% (+ - 14.4%) Africa (subcontinents various)

and 58.2% (+ - 15.3%) Africa (all West African)

that is 83.1%, total Africa

and 16.9% (+ - 1.2%) Europe (various sub-continents)

The following are possible population sets and their fractions,

probably on top

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.439 = 0.382 = 0.179 or Russian

Maasai = 0.152 Yoruba = 0.671 = 0.177 or Russian

The Ethiopian-= 0.129 = 0.711 = 0.160 Finland Yoruba or

The Ethiopian-Yoruba = 0.129 = 0.710 = 0.161 or Russian

Bantu Ke = 0.431 = 0.391 = 0.178 Mandenka or Finland

Maasai = 0.149 Yoruba = 0.675 = 0.176 Finland or

The Ethiopian-Yoruba = 0.116 = 0.734 = 0.150 Finland or

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.396 = 0.424 = 0.180 or Irish

T-Ethiopian Yoruba = 0.115 = 0.734 = 0.151 Finland or

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.433 = 0.389 = 0.178 Belarus

Western Europe, but it is also very possible.

3.2% Native American (European subtracts).

but in fact the European is probably British. And there

Native American 3.0% of unknown type. This is typical

African-(Euro) American.

Native American 3.0% of unknown type. This is typical

African-(Euro) American.

Doug McDonald

A custom fit is better than automatic:

214,911 autosomal-it-results.csv

Irish 0.1461 0.0259 0.7159 0.1122 Maya Yoruba The Ethiopian-or

Irish 0.1467 0.0256 0.7156 Na-Dene The Yoruba-Ethiopian or 0.1120

English 0.1431 0.0279 0.7146 0.1144 Maya Yoruba The Ethiopian-or

English 0.1435 0.0280 0.7143 Na-Dene The Yoruba-Ethiopian or 0.1142

Irish 0.1897 0.0255 0.1091 0.6758 Yoruba Maya Mandenka

214,911 autosomal-it-results.csv

Irish 0.1461 0.0259 0.7159 0.1122 Maya Yoruba The Ethiopian-or

Irish 0.1467 0.0256 0.7156 Na-Dene The Yoruba-Ethiopian or 0.1120

English 0.1431 0.0279 0.7146 0.1144 Maya Yoruba The Ethiopian-or

English 0.1435 0.0280 0.7143 Na-Dene The Yoruba-Ethiopian or 0.1142

Irish 0.1897 0.0255 0.1091 0.6758 Yoruba Maya Mandenka

French or Spanish is also possible, in the same amount, with the same probability.

The Oromo-Ethiopians stands for, but this is probably not real: it just means that the

African is somewhere bewteen part of Nigeria and Ethiopia., Very nearest Nigeria.

The Middle East (violet) on chromosomes comes from East Africa, they

are mixed with people of Arabia.

African is somewhere bewteen part of Nigeria and Ethiopia., Very nearest Nigeria.

The Middle East (violet) on chromosomes comes from East Africa, they

are mixed with people of Arabia.

The American general in the U.S.. The red spot (euro) in teh map

is in the wrong place.

is in the wrong place.

Doug McDonald

There are not many studies on my Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a this time, but these references should be helpful ..

References:

Y-chromosomal variation: Insights in the history of Niger-Congo groups:

http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/11/25/molbev.msq312.abstract

http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/11/25/molbev.msq312.abstract

Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1a in Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_E1b1a_ (Y-DNA)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_E1b1a_ (Y-DNA)

Popular Yorubua:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoruba_people

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoruba_people

The Druze People:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Druze

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Druze

The Yoruba list SNP was inferred from the presentation of dbSNP

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_viewBatch.cgi?sbid=856991

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_viewBatch.cgi?sbid=856991

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário